Language is always evolving, so it has residual organs. Here in South Africa we are in what is called a game reserve, but I think of it as a wildlife reserve. The term “game” is left over from when people like Ernest Hemingway and Theodore Roosevelt went on safari to hunt “big game.” The vast majority of people who go on safari today are going to observe and enjoy nature, to experience for themselves the staggering beauty of the African wilderness. It’s a life-changing experience just to breathe the same hearty atmosphere as Africa’s incomparable wildlife: elephants, rhinos, lions, leopards, giraffes, zebras, hippos, etc. Today’s safari-goers shoot massive numbers of photographs and videos.

We are on a 10,000-hectare reserve, roughly 40 square miles of open range. The animals are conditioned to seeing the safari vehicles, so they don’t run away when they see us. The antelope and other prey animals are wary and watchful. They draw back. The elephants are curious and want to engage. The lions, at the top of the food pyramid, couldn’t be bothered. They barely notice us.

Our guide explained that the lions see our Landcruiser as a single entity. They don’t focus on the individual people in the vehicle, and we don’t register to them as prey. If they notice us at all, it’s with mild annoyance, as they might regard insects swarming around their heads. So, it’s possible to get very close to them, but not be in danger.

But though you’re not in danger, it might make your breath stop to find yourself a few feet from a lioness as she saunters by, her jaw hanging, revealing gigantic canines.

The big animals, especially the predators, are the central focus of our search for wildlife. But that’s only part of it. The whole experience of riding around the African veldt, observing the animals and plants and taking in the breathtaking vistas, is exhilarating.

The guides want to show you the entire range of wildlife, but they have to find them. You never know when you go out what you’ll see. It is hoped that over two or three days you’ll see the whole range of what’s there.

Everyone wants to see “the Big Five,” even if they can’t name them. That’s another holdover from big game hunting. The Big Five were the big animals that were the most dangerous to hunt on foot: lion, leopard, rhinoceros, elephant and buffalo. But they are only a few of the many fascinating animals you see in the African bush.

Many others are just as exciting to see, and often more beautiful. The giraffes are fantastic! They are gigantic, but elegant and graceful. You can’t sneak up on them. Whenever you come across a giraffe, she’s already looking at you. They know you’re there.

Zebras are nature’s Op Art. Seeing a herd of them in the hot sun can make your eyes spin. And you wonder, what in evolutionary history could have caused them to develop those wild stripes?

In the bush, almost everything I learned as a child about animals falls by the wayside when it collides with the reality encountered.

These days science is constantly coming up with new findings that wipe out earlier understandings of animals. We continue to learn that they are more intelligent and have greater capacities than we have previously known.

With the endless stream of videos of animals on social media, I often see behavior that I would not have thought possible. Animals are individuals, like people. They don’t read the books or follow the rules about how they are supposed to behave.

In the 20th century it was believed that giraffes don’t make a vocal sound. It seemed strange that they were mute. But now it is known that they do communicate with sound, “infrasounds” below the range of human hearing.

Starting from the elementary: “The pig goes ‘oink,’ the horse goes ‘nay,’ ” most of the conventional wisdom I learned about animals has proved to be false or over simplistic.

The lions are at the top of the list of things people want to see. The sight of a lion is rare compared to the sight of wildebeests and zebras, which tend to be numerous in the bush. The game drives are usually structured around the goal of finding the rarer animals. But while you’re searching for the big predators, you are taking all the wondrous sights of the wilderness, the uniquely African landscapes, the sunsets and the great variety of prodigious plants and animals. And while you are observing, you’re getting a running commentary from a real expert about what you are seeing.

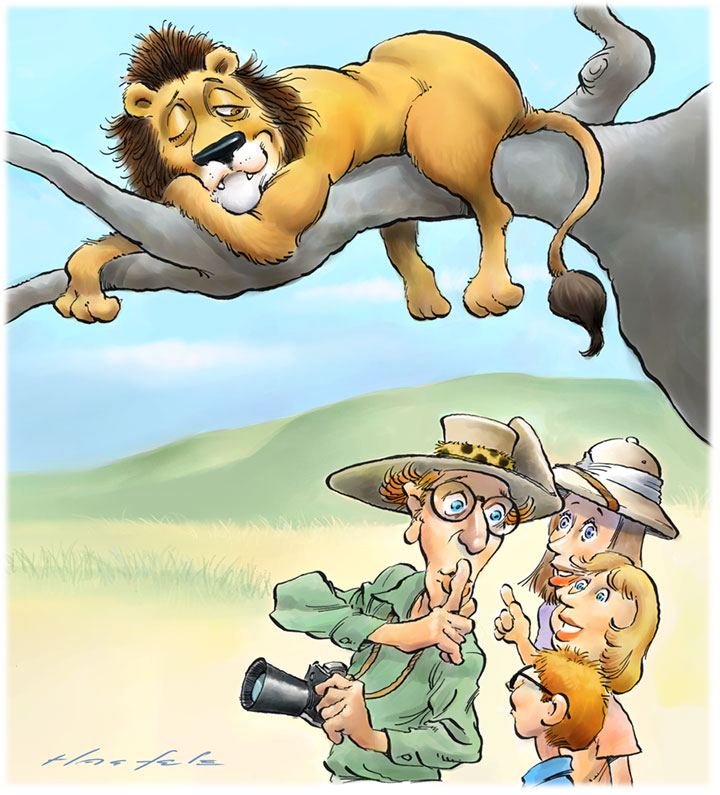

As we were driving across the plains searching for some lions that had been seen in the area, our guide said he spotted something in a solitary tree standing alone on the grassy range.

I was confused. “A lion?” That didn’t make sense. Lions don’t hang out in trees. Was he referring to a leopard? That would make more sense.

He didn’t answer. He was still looking at the tree to try to make out what he was seeing as we drove closer.

It turned out it was a lion. He could make it out, through the leaves and branches. But wait! There was another one. There were two lions, hanging out in a tree. That’s not something lions usually do. But it turns out, sometimes they do. And on this day, these lions decided to do that. They do not abide by the rules. Lions as a species are not tree climbers, as the leopards are, for example. But they can, and in this case, they did. Like us, they are still evolving, adapting, exercising choice. In the bush, nature is constantly presenting you with novelty.

We were only getting discreet glimpses of a paw, or the end of a flopping tail showing through leaves. Then one of the lions climbed down and unveiled his majestic figure and thick, dark mane.

The sight was stirring! What a magnificent beast he was! He stood haughtily, as if posing, though not for us, certainly. The lion is not called the king of beasts for nothing. They definitely have that regal bearing.

He walked toward a female he had seen. But she was 50 yards from him and walking away, so he gave up and stood still. We had had our lion sighting. Now it was getting to be time for our sundowner.

I had seen a pride of lions feasting on a freshly killed buffalo, so I was surprised to see two buffalo accost a lioness who was trying to catch some relaxation in the shade. They decided it was their territory, and they weren’t having it. They chased her off, and she went sulkily away. But wait! Doesn’t that violate the order of the food chain?

The thing that most disrupted my understanding of nature was when I saw a wildebeest dance up toward a lion, taunting it. I had never imagined such a gutsy thing. Wildebeests are not supposed to do that. They are the prey. Aren’t they are supposed to run away, to save their skin? How does that fit into the Darwinian struggle for survival in the wilds? That wildebeest earned my undying love for that act of bravado. It made no sense to me. But it forced me to expand my ideas of what is possible.

That’s the amazing thing about the African bush. It takes you right up face to face with nature in the wild, uncaged and unfenced. And it’s beyond anything you imagined. Nature casually disregards the laws of nature.

Your humble reporter,

Colin Treadwell

I must say that I like reading Colin’s travel guide blog. Please keep him on your team.

Thank you,

Kurt