As an American traveler to Africa I developed in reverse. Most Americans first travel to South Africa to see the great wildlife, then discover the culture. Many of them return to experience more of that, because the cultural experience is deep and broad, and is not exhausted in one trip.

My main interest initially was culture. But when I went on safari and saw the animals in their natural habitats, it was a revelation that profoundly changed my worldview. The wildlife changed my perspective on people.

Discovering Africa

Discovering Africa

Like most Americans I had only a sketchy knowledge of Africa for most of my life. My first impressions as a child came through movies, in which Africa was only an exotic setting for a mythical adventure, and told little about Africa.

I heard the occasional Africa news story that surfaces in our daily dosage of bad news, usually about some flood, famine, disease outbreak, war or terrorist attack. The image of Africa in the news media was almost always bleak. Unfortunately, the news footage is all of Africa that many Americans ever see. And it is nothing like the experience of going to Africa.

The Human Side

When I talk about culture, I’m talking about all the human aspects of a place, not just the culture of museums or concert halls, but all the creations and artifacts of the people and the way they live.

It’s hard to grasp how huge and diverse the African continent is. Only Asia is larger. America could fit in Africa three times over. All around Africa’s edges it was colonized by the empires of Europe and the Middle East. The European and Islamic cultural influences spread into the continent, mixed with the various indigenous cultures and with each other. The result is a fascinating pastiche of cultures and cultural hybrids set against an amazing and varied natural landscape.

Most of the colonization of Africa took place in the 19th and early 20th centuries. But some was much earlier. Cape Town, South Africa, was established in the 1652. Its rich multicultural blending goes back hundreds of years.

Stellenbosch, the wine country north of Cape Town, was settled by the Dutch in 1680, then developed for vineyards by French Huguenots, who had fled France to avoid beheading. They brought the French wine culture with them. That is characteristic of the kind of cultural blending that took place across South Africa as people converged there from all over the world.

Music and the African Soul

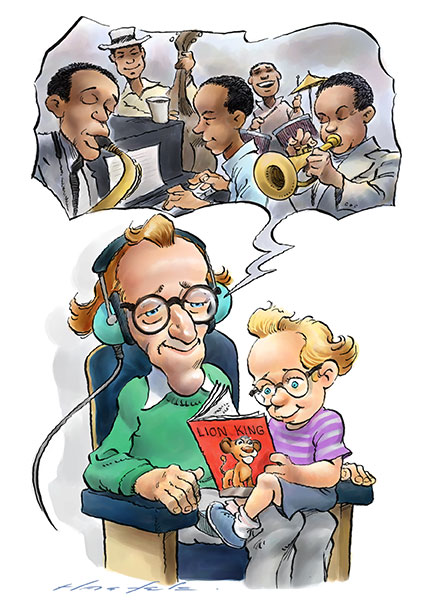

My interest in African culture started with music. Music was one of my main interests, and it was impossible to grow up listening to the rich cultural melting pot of American popular music without noticing an extremely strong contribution from the African part of American culture.

Since so many of my favorite musicians were African American, my attention was drawn to Africa. I wanted to find out what music was like in Africa, and to discover the African roots of the African American music I loved.

Gradually my attention gravitated toward South Africa. I heard of Hugh Masekela and Miriam Makeba, big stars from South Africa who had hits in America. In the ‘80s, Paul Simon recorded his album “Graceland” in South Africa with South African musicians.

Then there was Disney’s “The Lion King” on Broadway, which set the songs of Elton John and Tim Rice to the backing of African ensembles and choirs. That introduced me to African choral music, a product of the cultural mixing between the Welsh missionaries, with their famous choirs, and the polyrhythmic forms of indigenous African music, producing a vibrant hybrid with a tremendous power to uplift the spirit.

It really came together for me with a documentary film called Amandla: A Revolution in Four-Part Harmony, which showed the role of music as a vital force during the struggles to overthrow apartheid. I highly recommend the film, as well as the soundtrack, which is available on CD or as a playlist on Spotify.

Using the power of cinema to take you places, that movie showed a vivid glimpse of South African culture. It included some old black-and-white footage of a suburb of Johannesburg, South Africa, called Sophiatown. It was a cultural center that produced a number of noted musicians, authors, artists and activists. When the apartheid government came to power in 1948 it decided that Sophiatown violated its rules of keeping the races separate, and in 1955 it bulldozed the town.

The cinematic images of Sophiatown in the early ‘50s provided a tantalizing glimpse of a lively, sophisticated and fun culture. It showed that South Africa had developed its own flavors of jazz, dancing, clothing styles and literature. The film went on to show how the musical styles evolved in tandem with the evolving social struggles under the harsh apartheid system. I saw a vibrant, rich culture that was uncannily parallel to ours in America. I became determined to see South Africa for myself.

The film made the apartheid struggle understandable to me for the first time. It put the story of Nelson Mandela into a historical context and helped me understand why he was such an extraordinary leader. Most South Africans believe that Mandela, by his strength and moral authority, almost singlehandedly kept the political turmoil in South Africa from becoming a bloody civil war.

I was struck by the resonance between South Africa and America, and found the parallels to be illuminating. It was almost a “separated at birth” discovery to find a culture so similar to ours, yet so strikingly different.

New Amsterdam (later New York) was founded in 1624 by the Dutch West India Company; Cape Town was founded in 1652 by the Dutch East India Company. Both colonies were taken over by the British. Both countries had cultural clashes among different ethnic groups. America had cotton and slavery; South Africa had gold and apartheid. Both countries attracted people from all nationalities and ethnicities, who became part of the cultural fabric.

South African history is intertwined with American history. Martin Luther King drew from the nonviolent resistance philosophy developed by Mahatma Ghandi in South Africa before he took it back to India. Then King’s influence spread back to South Africa and helped the South Africans in their own struggles against racial discrimination.

Experiencing South Africa

I finally made it to South Africa to experience it for myself. I attended the Cape Town Jazz Fest, where I heard a selection from the broad swath of South African music. I was exhilarated by the high energy of Africa, the bright colors, and the innovation generated by multicultural cross fertilization.

At the Apartheid Museum I saw a graphic and detailed presentation of the history of apartheid, from its rise in 1948 until it collapsed with the first democratic election in 1994.

I visited the prison on Robben Island off the coast of Cape Town, where Mandela was imprisoned for 18 of his 27 years in prison. The guide there had been an inmate while Mandela was there. His descriptions gave us a tangible connection to the experience.

I saw the cell Mandela lived in, barely long enough for a big man to stretch out in. I saw the conditions under which he lived, the kinds of rocks he had to break as part of his sentence of hard labor.

Mandela is one of the great heroes of our times. It was thrilling to follow his footsteps through many sites associated with his life: his modest home in the township of Soweto, his law office in Johannesburg, and the place where he was captured in Kwazulu-Natal province, where there is now an epic sculpture in his honor.

Focusing on South Africa gave me a taste of the kind of colonial history that played out across Africa. The entire continent is teeming with cross-cultural dynamism. It’s not like the images in the news media. It’s an extremely exciting place culturally. I’ve had a taste, and I see there’s a huge amount more waiting to be discovered.

I wish more Americans would avail themselves of the tremendous cultural resources that could be theirs in Africa.

Your humble reporter,

A. Colin Treadwell